Ever wondered why William Shakespeare is the greatest inventor of all time? He invented the English language. Almost. Few people know that Shakespeare invented nearly 3000 words, most of which are still in use today. But what does it really mean to “invent words”? Before we dip our noses into Shakespeare’s works let us flip through the history book to understand why and how he did it.

English before Shakespeare

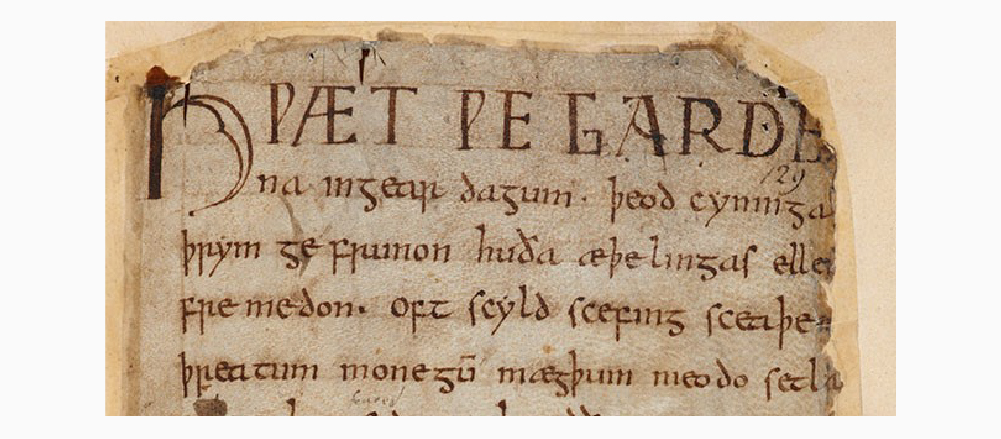

When William the Conqueror, the Duke of Normandy, conquered England in 1066, the language of the land was Old English, a mixture of old Germanic and Celtic words originating from the languages spoken by the three tribes invading the British Isles – the Angles, Saxons and the Jutes, who spoke similar languages.

Each of these tribes left its mark on the language. For example, the Angles came from Engaland and spoke Englisc, which served as the basis for words like “England” and “English.” Other old English or Anglo-Saxon words include terms referring to the human body, animals, the weather, farming, family relationships, colours, landscape, and activities like cooking, drinking, sewing, hunting, eating, and carpentry:

● Abide, above, ale, alive, apple, awake, axe, be, back, bed, bird, body, brother, back, blood, bed, can, carve, child, chicken, clean, cold, cup, daft, daughter, dead, deer, door, drink, dusk, each, ear, elbow, end, evening, evil, eye, fair, fall, feather, find, fish, fox, friend, game, gate, gold, hand, high, ground, green, good, god, gold, ground, hammer, harbour, hand, high, honey, house, husband, ice, I (the 1st person singular pronoun), if, in, island, it, itch, keen, keep, kind, king, kiss, kind, king, knife, knot, ladle, land, laugh, lip, listen, long, love, strong, water, and many more.

Excerpt from Beowulf, English epic poem believed to have been written around the 900s – 1000s AD

Securing a sounding victory at Hastings, William the Conqueror brought not only a new rule to England but also a new language – Norman/French, which became the language of the court. This explains the presence of so many French words in English today. Most of them are legal and military terms but also relate to cooking and court activities, such as “chivalry”, “chivalrous”, or “majesty”. Below are a few more examples of Norman words to delight in:

● Accuse, adultery, archer, assault, asset, bacon, bail, bailiff, beef, butcher, button, comfort, court, courtesy, cricket, curfew, custard, defeat, dungeon, duty, eagle, elope, embezzle, enemy, error, evidence, exchequer, fashion, felony, fraud, gallon, goblin, gourd, grammar, grease, grief, grocer, gutter, haddock, havoc, Hogmanay (a Scottish New Year’s festival nowadays), honour, injury, jettison, joy, judge, lease, lever, leisure, liable, libel, liberty, liquorice, mackerel, marriage, matrimony, mayhem, mutton, noble, noun, nurse, occupy, nurse, odour, parliament, pedigree, penthouse, perjury, pinch, platter, pleasure, pork, and a lot more.

While Anglo-Norman courtiers spoke French as their first language, the populace continued to speak English. Often the difference in spoken language marked a difference in class. This can be observed in jobs of the time, with barbers and shoemakers preserving their Anglo-Saxon names whilst tailors and merchants adopted a French trade name.

In time, usage of both French and English gradually obliterated the differences between the two eternal rivals (at least, in terms of vocabulary), and an Anglo-Norman combination of the two vernaculars became the language of the realm.

There are approximately 10,000 Norman French words in English, of which 7,000 are currently being used in modern English. However, a cluster of words does not make a rich literary language. When young William Shakespeare entered the stage (pun intended), English as a language was “ripe” for coinage.

Love’s labour NOT lost

Less than 100 years old in Shakespeare’s time, English lacked standardisation, and official documents were still being written in Latin. No dictionary had been published, no grammar texts existed and English was not officially studied in schools. Not to mention that English syntax rules were volatile and the vocabulary limited. Here is an example from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight written by an anonymous author allegedly from the North-West Midlands, considering the form of expression.

Now neez þe Nw ere, and þe nyt passez,

Þe day dryuez to þe derk, as Drytyn biddez;

Bot wylde wederez of þe worlde wakned þeroute,

Clowdes kesten kenly þe colde to þe erþe,

Wyth nye inoghe of þe norþe, þe naked to tene; 5

Þe day dryuez to þe derk, as Drytyn biddez;

Bot wylde wederez of þe worlde wakned þeroute,

Clowdes kesten kenly þe colde to þe erþe,

Wyth nye inoghe of þe norþe, þe naked to tene; 5

Þe snawe snitered ful snart, þat snayped þe wylde.

Þe werbelande wynde wapped fro þe hye,

And drof vche dale ful of dryftes ful grete.

Þe leude lystened ful wel þat le in his bedde,

Þa he lowkez his liddez, ful lyttel he slepes; 10

Þe werbelande wynde wapped fro þe hye,

And drof vche dale ful of dryftes ful grete.

Þe leude lystened ful wel þat le in his bedde,

Þa he lowkez his liddez, ful lyttel he slepes; 10

Bi vch kok þat crue he knwe wel þe steuen.

Deliuerly he dressed vp, er þe day sprenged,

For þere watz lyt of a laumpe þat lemed in his chambre;

He called to his chamberlayn, þat cofly hym swared,

And bede hym bryng hym his bruny and his blonk sadel;

Þat oþer ferkez hym vp and fechez hym his wedez, 16

And grayþez me Sir Gawayn vpon a grett wyse.

Fyrst he clad hym in his cloþez þe colde for to were,

And syþen his oþer harnays, þat holdely watz keped,

Boþe his paunce and his platez, piked ful clene, 20

Þe ryngez rokked of þe roust of his riche bruny (i);

And al watz fresch as vpon fyrst, and he watz fayn þenne

to þonk;

He hade vpon vche pece,

Wypped ful wel and wlonk; 25

Deliuerly he dressed vp, er þe day sprenged,

For þere watz lyt of a laumpe þat lemed in his chambre;

He called to his chamberlayn, þat cofly hym swared,

And bede hym bryng hym his bruny and his blonk sadel;

Þat oþer ferkez hym vp and fechez hym his wedez, 16

And grayþez me Sir Gawayn vpon a grett wyse.

Fyrst he clad hym in his cloþez þe colde for to were,

And syþen his oþer harnays, þat holdely watz keped,

Boþe his paunce and his platez, piked ful clene, 20

Þe ryngez rokked of þe roust of his riche bruny (i);

And al watz fresch as vpon fyrst, and he watz fayn þenne

to þonk;

He hade vpon vche pece,

Wypped ful wel and wlonk; 25

Later, the story was “translated” and revamped by Geoffrey Chaucer, who included it in The Canterbury Tales, perhaps the first successful, well-rounded piece of literature written in English before Shakespeare. Written in London Middle English dialect, Chaucer’s version of the story is considerably lighter, although it still preserves numerous Old Norse words and unusual verb forms:

Now the New Year draws near, and the night passes,

the day takes over from the night, as God commands;

but fierce storms wakened from the world outside,

clouds bitterly threw the cold to the earth,

from the north with much bitterness, to torment the naked; 5

the snow, which nipped cruelly the wild creatures,

came shivering down very bitterly;

the wind blowing shrilly rushed from the high (ground),

and drove each valley full of very large (snow)drifts.

The man who lay in his bed listened very carefully,

although he locks his eyelids, he sleeps very little; 10

by each cock that crew he was reminded of (lit. �knew well�) the appointed day. Before the day

dawned, he quickly got up,

for there was light from a lamp which shone in his bedroom;

he called to his chamberlain, who promptly answered him,

and bade him bring him his mailcoat and his horse-saddle;

the other man rouses himself and brings him his clothes, 16

and Sir Gawain is prepared (lit. �one prepares�) in a magnificent manner.

First he dressed himself in his clothes to protect (himself) from the coold,

and then his other armour, which was preserved carefully,

both his stomach-armur and his steel plates, polished very brightly,

the rings of his splendid mail-shirt made clean from rust (i); 20

and everything was clean as in the beginning, and he was desirous then to thank (his servants?);

he had on him each piece (of armour),

very well wiped and noble; 25

the most handsome (man) as far as Grece,

the warrior made (one) bring his horse.

for there was light from a lamp which shone in his bedroom;

he called to his chamberlain, who promptly answered him,

and bade him bring him his mailcoat and his horse-saddle;

the other man rouses himself and brings him his clothes, 16

and Sir Gawain is prepared (lit. �one prepares�) in a magnificent manner.

First he dressed himself in his clothes to protect (himself) from the coold,

and then his other armour, which was preserved carefully,

both his stomach-armur and his steel plates, polished very brightly,

the rings of his splendid mail-shirt made clean from rust (i); 20

and everything was clean as in the beginning, and he was desirous then to thank (his servants?);

he had on him each piece (of armour),

very well wiped and noble; 25

the most handsome (man) as far as Grece,

the warrior made (one) bring his horse.

With a language so “experimental” and a literature only timidly blooming into expression, Shakespeare gave it memorability.

Words and phrases that Shakespeare invented and we use

In his sonnets and plays, Shakespeare used a whooping 29,066 unique words. Most English speakers today use between 7,500 and 10,000 unique words in writing and speech. Many of the words and phrases that Shakespeare introduced are still used today. Here is a list you can relish:

● Accommodation, aerial, amazement, apostrophe, auspicious, baseless, bloody, bump, castigate, changeful, clangor, control (noun), countless, courtship, critic, dexterously, dishearten, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, exposure, fitful, frugal, generous, gloomy, gnarled, hurry, impartial, inauspicious, indistinguishable, invulnerable, laughable, lapse, lonely, majestic, misplaced, monumental, multitudinous, obscene, palmy, perusal, pious, premeditated, radiance, road, sanctimonious, seamy, sportive, submerge, suspicious.

Some of the proverbs and catchphrases that we use today we owe Shakespeare:

● All that glitters isn’t gold

● Barefaced

● Break the ice

● Breathe one’s last

● Brevity is the soul of wit

● Catch a cold

● Clothes make the man

● Disgraceful conduct

● Dog will have his day

● Eat out of house and home

● Elbowroom

● Fair play

● Fancy-free

● Flaming youth

● Foregone conclusion

● Frailty, thy name is woman

● Give the devil his due

● Green-eyed monster

● Heart of gold

● Heartsick

● Hot-blooded

● Housekeeping

● In a pickle

● It smells to heaven

● It’s Greek to me

● Lackluster

● Leapfrog

● Live long day

● Long-haired

● Method in his madness

● Mind’s eye

● Ministering angel

● More sinned against than sinning

● Naked truth

● Neither a borrower nor a lender be

● One fell swoop

● Pitched battle

● Primrose path

● Strange bedfellows

● The course of true love never did run smooth

● The lady doth protest too much

● The milk of human kindness

● To thine own self be true

● Too much of a good thing

● Towering passion

● Wear one’s heart on one’s sleeve

● Witching time of the night

Whether we refer to Shakespeare’s unique ability to create words as “coinage”, “minting” or simply “inventing” vocabulary matters less. What he did with words nobody else before him nor after ever thought of doing. And this is what’s truly remarkable.

Shakespeare through the looking glass

Nothing is at random in Shakespeare’s works. Although many of his modern readers quickly jump to the Arden modern English translation of the bard’s complete works to fully absorb the nuance and meaning of his language, Shakespeare’s contemporary audience would immediately grasp every twist and turn of his scenarios. How so?

That’s simple. Shakespeare was part of a movement famous at the time for introducing prose into plays. His first plays were written in rhyming verse – Henry VI Part 1, Two Gentlemen from Verona, Titus Andronicus, and others, written around 1592.

By comparison, his later-day plays favoured a more conversational, natural speech style, making it easier for the Elizabethan audience to grasp the message. Furthermore, the words and phrases Shakespeare created could be intuitively inferred from the context. For example, the word “congreeted” means “to receive or acknowledge someone”, as eloquently suggested by the association of the prefix “con” (having the meaning of “with”) and “greet” (meaning to receive someone with an open heart).

Therefore, a line like the one below extracted from Henry V did not pose any challenges for the playwright’s audience:

“That, face to face and royal eye to eye.

You have congreeted.”

Shakespeare is also well-known for turning nouns into verbs. Few of his modern readers today know that he was the first author to use “friend” with a verbal meaning, leaving Meta’s father Mark Zuckerberg 395 years behind (you’ll do the math).

“And what so poor a man as Hamlet is

May do, to express his love and friending to you”

(Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5)

Sometimes, the Elizabethan bard would scoop his extensive Latin vocabulary and borrow words:

“His heart fracted and corroborate.”

(Henry V, Act 2, Scene 1)

The Latin word “fractus” here has the meaning of “broken”. Replacing the “-us” suffix with the “-ed” verbal suffix, Shakespeare coined a new word.

Is coinage really Shakespeare’s invention?

No. William Shakespeare wasn’t the first writer or person to create new words. In fact, it is quite common that new words creep into a language. “Official” dictionaries add new words frequently. Meriam-Webster, for example, lately added new words and phrases such as:

● Bokeh, elderflower, fast fashion, first world problem, ginger, microaggression, mumblecore, pareidolia, ping, safe space, wayback, wayback machine, woo-woo.

So, coinage was not unique to Shakespeare. It’s been with us all along. Then, what do English speakers owe Shakespeare?

Shakespeare’s contribution to the English language

Before Shakespeare, the language was considerably poorer and its vocabulary way too scarce to support a genius like him. Once Shakespeare found his muse, the English language started to grow. According to Edmund Weiner, Deputy Chief Editor for the Oxford English Dictionary:

“The vocabulary of English expanded greatly during the early modern period. Writers were well aware of this and argued about it. Some were in favour of loanwords to express new concepts, especially from Latin. Others advocated the use of existing English words, or new compounds of them, for this purpose. Others advocated the revival of obsolete words and the adoption of regional dialect.”

William Shakespeare’s collected works count a total of 31,534 words. Regardless of the richness or scarcity of the Elizabethan English vocabulary, clearly, the bard mastered and mustered most, if not all of it. Researcher John Kottke estimates Shakespeare’s vocabulary must have counted virtually 66,534 words, suggesting that Shakespeare was pushing the boundaries of language as he and his contemporaries knew it. He simply had to make up new words if he was to write.

So, what are the best words that Shakespeare invented? It’s a very difficult decision. All of the bard’s coinages have almost unwittingly crept into usage and are widely used today, like anchovy, baseless, batty, beachy, belongings, birthplace, black-faced, bloodstained, bloodsucking, blusterer, bodikins, braggartism, brisky, worn out, watchdog, varied, ell-read, water drop, and even “zany” ones like zany. Wow! Is there any word that Shakespeare did not invent? Hold that thought until next time.

Meanwhile, if you find it difficult to translate or transcreate any of these words and phrases in your language, drop us a line. We’ll be more than happy to lend a hand.